An analysis of the (possible) reasons for the decline in public participation in nonviolent movements and peaceful protests, based on data from February 2024 and February 2025

The Introduction

The military has been violating the most fundamental of human rights, the right to freedom of thought and expression. When the spring revolution started, they tried to stop peaceful protests using violence. As more people joined non-violent movements, the military responded with more violence – beating, arresting, and jailing protesters, especially in early 2021. Through these violent actions, they created fear among people who opposed their illegal takeover, whether those people expressed themselves through writing, speaking, or just thinking differently.

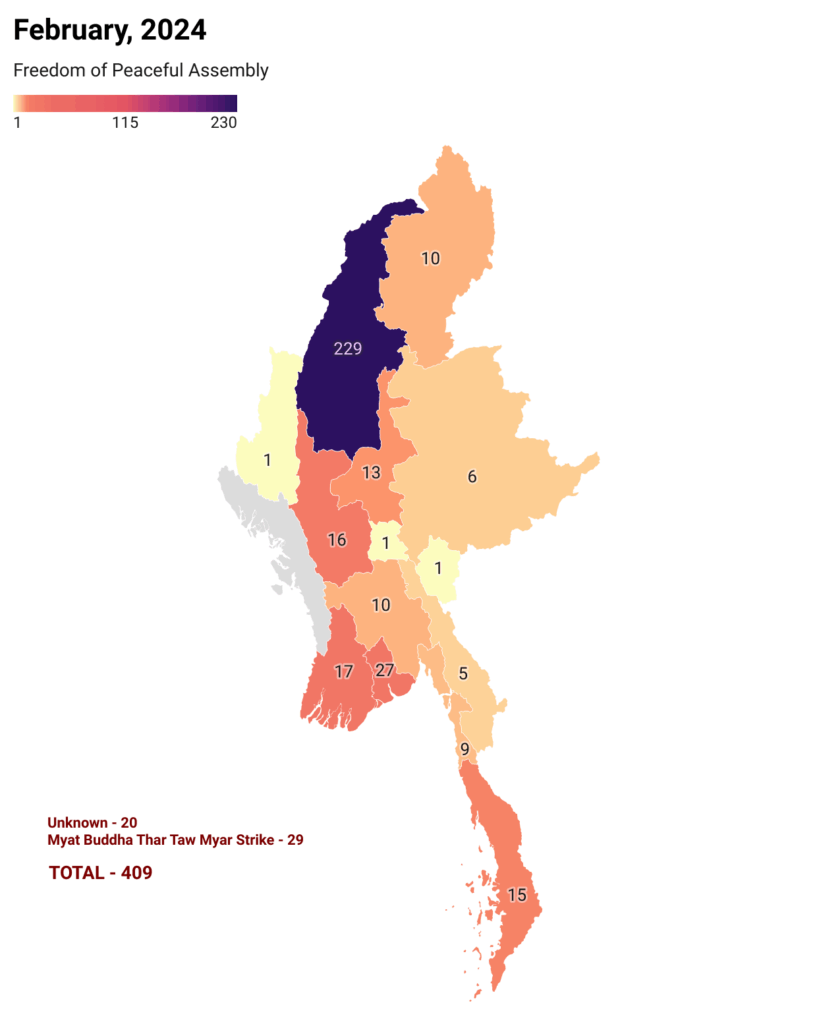

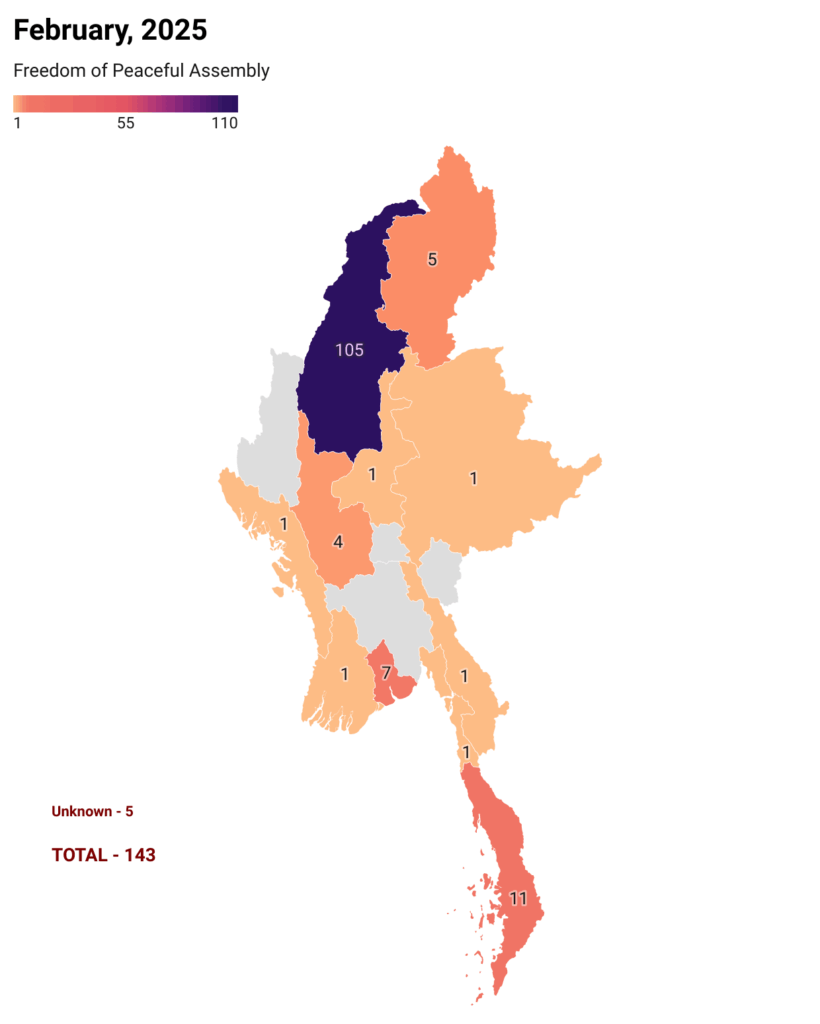

This document analyzes and compares the possible reasons for the decreased public participation in non-violent movements and peaceful protests and assemblies, based on non-violent public movements and peaceful demonstration processes carried out by the public in February 2024 and February 2025. Some pro-military demonstrations also emerged during these February months, but they are not included or accounted for in this document.

Looking over the ongoing non-violent movements carried out by the people during these past four years, it can be seen that the Myanmar military’s complete takeover has not been successful. Despite ongoing oppression and restrictions, protests against the military – such as strikes, campaigns, silent strikes, and flash-mobs have taken place regularly, especially every February. Therefore, in February 2024 and 2025, depending on the political situation on the ground, we can see ongoing changes in public movements, as well as shifts in the military’s political strategies and the beliefs held by the civilians. Furthermore, it is possible to keep examining the opinions and perspectives of the revolutionary groups on the right to peaceful assembly and peaceful protest.

Findings

Research findings reveal that from late January 2024, military forces, accompanied by affiliated entities such as fire department personnel, administrative officials, and departmental staff, began patrolling communities in vehicles. During these patrols, they broadcast religious prayers while simultaneously threatening to arrest business owners who did not open their shops. This coordinated intimidation strategy was designed to increase visible public activity and create an appearance of normalcy, effectively undermining the protest movement’s silent strike tactics. Despite these threats, throughout February 2024, over (409) non-violent public movements and protests against the military dictatorship took place across various regions in Myanmar. According to the collected information, there have been (62) Silent Strikes, (248) Protests with processions, (12) Flash-Mob, (33) General Campaigns against the coup, (20) White Campaigns, (5) Prison Strikes, and (29) Monk-Led Protests (Buddah Tar Taw Myar Strike).

By February 2025, documentation revealed approximately (143) instances of non-violent civil resistance activities throughout the country. Analysis of the geographic distribution indicates that the Sagaing Region emerged as the epicenter of resistance, accounting for roughly (105) recorded demonstrations against the military regime. This significant concentration of protest activities in Sagaing suggests the region’s strategic importance within the broader resistance landscape, despite escalating repression tactics deployed by authorities. According to the records, in February 2025, there were (126) Protests with processions, (7) Flash-Mob, and (10) General Campaigns against the coup.

(The map showcasing the peaceful public demonstrations and non-violent civilian movements carried out by the people in February 2025)

(Note: The numbers mentioned above have been calculated based solely on the data obtained from the Athan- Myanmar Activist Organization)

A quantitative analysis of civilian-organized non-violent movements between February 2024 and February 2025 reveals a marked decrease in protest frequency and participation. Particularly noteworthy is the substantial decline in “Silent Strikes” – a form of collective action consistently employed since the military’s February 2021 seizure of power. This diminishing resistance can be attributed to the regime’s systematic campaign of violence against peaceful demonstrators, characterized by targeted arrests, imprisonment, and extrajudicial killings of movement leaders and participants. Such brutal counterinsurgency tactics have effectively cultivated an atmosphere of profound fear among the civilian population, substantially impeding their capacity and willingness to engage in further collective action. Another reason for the drop in public participation in peaceful protests and non-violent civil movements is the Public Military Service Law, which was announced by the military on February 10, 2024. Since the law was introduced, many young people have been fleeing the country to avoid being forced into military service.

From Non-Violence to Armed Resistance

The public has gradually recognized that armed resistance offers a viable alternative to non-violent protest under the “Resist without Oppression” ethos, particularly when confronting a military that seized power through brute force. This strategic pivot explains the ongoing clashes between revolutionary forces and military units – fundamentally, these confrontations represent efforts to reclaim the authority wrongfully taken from citizens. While visible public demonstrations have noticeably declined since previous years, our research indicates that resistance persists in adapted forms. Citizens continue to oppose the military regime through whatever means are available to them in their specific contexts and localities. Rather than signaling defeat, this evolution reflects a pragmatic response to escalating repression and changing tactical realities on the ground.

Military Escalation and Revolutionary Response

As stated above, while the public engaged in non-violent movements, the military resorted to full-scale offensives against regions under the control of local defense forces and ethnic revolutionary groups following the armed resistance. This included carrying out sweeping assaults, burning entire villages, committing massacres, and conducting airstrikes. However, in recent times, with the involvement of the people, financial support, and endorsements, the local defense forces and ethnic revolutionary groups have strengthened their connections and organization compared to before. As a result, they have been able to conduct coordinated operations targeting the oppressive military, and it is observed that revolutionary forces currently control 96 townships.

Shifting Media Focus and International Attention

This point highlights how, over time, the public opposing the military dictatorship in Myanmar is increasingly caught between choosing non-violent resistance and armed struggle, with a growing shift toward armed resistance. As a result, local news outlets tend to focus more on reports of clashes between the military and resistance groups, rather than on stories about peaceful protests or civil movements. Meanwhile, international attention on Myanmar’s Spring Revolution has faded, leading to a drop in support and aid from global organizations. Despite this, in areas controlled by local defense forces and ethnic revolutionary groups, peaceful resistance—such as protests, awareness campaigns, and other anti-junta activities—continues to thrive. In fact, studies show that these non-violent efforts are more frequent in these regions compared to those still under tight military control.

Legal Framework Challenges & Collapse of Justice System

The law amending the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act was first enacted under President U Thein Sein on June 24, 2014, and later reaffirmed by the National League for Democracy government on October 4, 2016. The purpose of this law was to provide some level of protection for the rights to peaceful assembly and protest. However, there are still noticeable gaps in how well these rights are protected. A closer look at the law’s provisions shows weaknesses in legal safeguards for peaceful gatherings and ongoing restrictions on freedom of expression. This suggests that further revisions and improvements are still necessary.

Since the military coup, Myanmar’s judicial system has completely collapsed. Laws are no longer enforced properly, and even lawyers and judges have lost the ability to carry out their duties. With the rule of law absent and the military placing itself above the law—changing and manipulating it at will—the rights to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression have been severely threatened. Meanwhile, although the people have continued their non-violent protests and anti-junta movements for over four years, the lack of strong, effective action from international organizations in response to ongoing military atrocities has pushed many oppressed civilians to turn their focus toward armed resistance.

Pre-Existing Weaknesses and New Challenges & Concerning Incidents in “Liberated Areas”

A review of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression in Myanmar shows that even under the civilian-led democratic government, the laws surrounding public gatherings and protests did not fully protect the people’s rights. After the military coup, these shortcomings became even more apparent as the military blatantly ignored the law and carried out widespread acts of violence. At the same time, many revolutionary groups—though committed to building a free and fair federal union and opposing the military dictatorship—lacked a clear understanding of the values and importance of peaceful protest and civil resistance. This gap has contributed to the decline in public participation in non-violent movements and peaceful demonstrations against the dictatorship.

Several troubling incidents in “liberated areas” controlled by revolutionary forces highlight ongoing concerns. These include: (1) the shooting incident involving protesters in the MNDAA-controlled area in northern Shan State, Kutkai (2) the arrest of over 40-people who expressed their protest by the People’s Defence Force (PDF) in Sarlingyi Township, Sagaing Region (3) the arrest of 25-local women who staged a protest against a rare earth mining operation in the 7th Brigade area of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in Pangwa region, Hpare Village and (4) the arrest of six individuals, including members of the People’s Defense Force (PDF), Chiefs, and six people those engaged in civil disobedience, in Ye U Township. These cases raise serious questions about whether some revolutionary forces, after gaining arms and authority, may begin to mirror the oppressive tactics of the military—undermining the principles of peaceful protest and resorting instead to repression and control.

The Military’s Election Strategy

As noted earlier, non-violent public movements and peaceful protests against the military dictatorship have lost momentum due to oppressive and restrictive actions from multiple sides. In the aftermath, it has become clear that the military is now making a strong push to organize the general elections they plan to hold. This suggests that, faced with declining control over territory, the military sees elections as a way to reassert its authority. Observations indicate that the military is carefully implementing a strategy designed to gain international recognition by presenting itself as a legitimately elected government once the elections take place.